Dear Reader,

I love to work with authors who have gone deep on their subject, or who go the extra mile to report their story. Jennie Erin Smith upended her whole life to report this book.

She was drawn in by a medical mystery: For hundreds of years, the residents of isolated rural villages around Medellín, Colombia have been losing their memories before, inevitably, their lives are cut short in their forties or early fifties. In the 1980s, a Colombian doctor named Francisco Lopera discovered they carry a rare genetic mutation that causes early-onset Alzheimer’s. Then he spent the rest of his career building a world-class medical research program in this underdeveloped, intensely violent region. The families with the mutation got a crash course in modern science. Suddenly they became a key part of the effort to find a cure for Alzheimer’s.

For most of the last decade, Jennie Erin Smith, an award-winning journalist, has been deeply immersed in reporting this story. She has been living with these Colombian families. She attends their reunions, their doctor’s appointments, and their many, many funerals. She has been following the doctors who study them, too, as they conduct autopsies, present their findings at medical conferences, and embark on. The result is a book that transports readers to the streets of Medellín and the remote mountain villages perched high above the city. We follow the doctors and researchers overcoming incredible challenges to pursue the science. We see how the families’ lives are impacted by this cruel disease and by the demanding medical trials that dangle the prospect of a possible cure. Valley of Forgetting is an intricate, heartbreaking, and inspiring narrative, and it’s masterfully told.

I hope you find this beautiful book just as moving and compelling as I do.

Sincerely,

Courtney Young

Executive Editor, Riverhead Books

The riveting account of a community from the remote mountains of Colombia whose rare and fatal genetic mutation is unlocking the secrets of Alzheimer’s disease

“Powerful. . . . a poignant depiction of a community in crisis.” —Publishers Weekly

In the 1980s, a neurologist named Francisco Lopera traveled on horseback into the mountains seeking families with symptoms of dementia. For centuries, residents of certain villages near Medellín had suffered memory loss as they reached middle age, going on to die in their fifties. Lopera discovered that a unique genetic mutation was causing their rare hereditary form of early onset Alzheimer’s disease. Over the next forty years of working with the “paisa mutation” kindred, he went on to build a world-class research program in a region beset by violence and poverty.

In Valley of Forgetting, Jennie Erin Smith brings readers into the clinic, the laboratories, and the Medellín trial center where Lopera’s patients receive an experimental drug to see if Alzheimer’s can be averted. She chronicles the lives of people who care for sick parents, spouses, and siblings, all while struggling to keep their own dreams afloat. These Colombian families have donated hundreds of their loved ones’ brains to science and subjected themselves to invasive testing to help uncover how Alzheimer’s develops and whether it can be stopped. Findings from this unprecedented effort could hold the key to understanding and treating the disease, though it is unclear what, if anything, the families will receive in return.

Smith’s immersive storytelling brings this complex drama to life, inviting readers on a scientific journey that is as deeply moving as it is engrossing.

Praise for Valley of Forgetting

“Jennie Erin Smith writes with such narrative skill, such empathy and curiosity, such a strong sense of the place where science and people meet, that you come out with the feeling of having witnessed an extraordinary investigation into the mysteries of what makes us human.” —Juan Gabriel Vásquez, author of The Sound of Things Falling

“Valley of Forgetting is the masterfully told story of how, over the past four decades, a human drama of extraordinary significance has quietly unfolded in a rural province of Colombia. Jennie Erin Smith deserves a wide readership for this book that is at once revealing, unsettling, timely, and ultimately, deeply moving.” —Jon Lee Anderson, author of Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life and To Lose a War

“Jennie Erin Smith’s story of scientific detective work under impossible circumstances, and the people who offer up their trust and their brains, is harrowing, but also more exhilarating than you’d imagine a book about dementia could possibly be.” —Larissa MacFarquhar, author of Strangers Drowning: Impossible Idealism, Drastic Choices, and the Urge to Help

“Solid medical reportage with a hopeful conclusion that science may soon bring a cure for a devastating disease.” —Kirkus Reviews

Valley of Forgetting takes us from communities in the remote mountains of Columbia to the clinics and laboratories at the forefront of Alzheimer’s drug research. How did you come across this story?

I first took note of this story after watching a 60 Minutes segment in 2016. It was called “The Alzheimer’s Laboratory,” about Dr. Lopera and the Colombian families with early-onset dementia, and there were some things that stood out to me right away. All the people who were interviewed were at risk of having the mutation that causes Alzheimer’s by their mid-40s. And yet nobody said they wanted to know whether they carried it – which was weird and, I later learned, untrue. The researchers didn’t tell them, and they were discouraged from finding out. The other thing that I noticed was the title—“laboratory.” My immediate thought was, for whom? It all led to a broader desire to want to learn about the experience of these families, and of participating in research that might or might not benefit you.

How did Dr. Lopera come across this community? Can you speak to the challenges he was up against and his early studies?

Dr. Lopera discovered the first family in 1984, when he was a neurology resident at a public university hospital. A 49-year-old farmer came in from the countryside with advanced dementia, and his family reported that his mother had died of the same. What was always special about Dr. Lopera was his curiosity, and his willingness to get outside the clinic if he had to. He made a four-hour trip to the patient’s village, sat and sketched out their family trees, and discovered that the man’s brother was also sick. This was his first experience with the family would turn out to have 6,000 living members, making it bigger on an order of magnitude than any other family in the world with hereditary early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Until Dr. Lopera, they had been living in mountain towns around Medellin for more than two centuries, essentially unnoticed.

At the heart of the book are the families that are living with this disease. Can you tell us more about who these people are?

The families at the heart of this book—and Dr. Lopera’s research—have a common ancestor, and they have roots in a handful of rural towns that form a sort of chain to the north of Medellín. By now almost half of them live in the city, and some live in other cities or have left Colombia. With few exceptions, they are what people in Colombia would call “humilde,” which is a euphemism for poor, though younger generations do a little better. They are poor in part because they or their parents migrated from rural regions, often thanks to violence, and they didn’t really have the skills needed to compete in the city. The families with this genetic variant also tend to be white, which led to a lot of hypothesizing, back in the early 2000s, that their largely European heritage was what caused this rare mutation to flourish. Really, though, it was because they traditionally had so many children—in the 19th century and early 20th century it was not unusual for a family in this part of Colombia to have 15 or even 20. With each child having a 50% chance of inheriting the mutation, that’s a lot of chances for it to take hold in a community.

How has the research benefited the families who participated in the studies? How do they feel about being a part of these studies?

The families have benefited in that they’ve been exposed to interesting experiences, including international travel, and have been able to feel part of an important global effort. The research group led by Dr. Lopera also offers them help with things like hospital beds, diapers, and occasional deliveries of groceries. The families participate in workshops about Alzheimer’s and caring patients, and they do get psychological counseling, at least as part of certain studies. They do not, however, benefit economically from their participation.

Their feelings about taking part in research were all over the map. Some considered Dr. Lopera nothing short of a saint, while others spread rumors that he was secretly selling autopsy brains abroad. In general, I found older generations to be appreciative of Dr. Lopera and his efforts, and quick to say yes to studies even without knowing much about them. The younger generations—which have more education—have become increasingly skeptical, in part because they didn’t see their parents much helped by taking part.

You’ve been reporting on this book since 2017. Can you tell us more about where researching this book has taken you? Has reporting this book changed your perspective on medical research and how it’s conducted?

Before I began work on this book, I did a lot of medical reporting that involved going to conferences and listening to presentations. I had never spent time with patients and doctors in a clinic. Part of that was because privacy laws in the U.S. are so stringent, which they aren’t in Colombia. That gave me an important look at the interactions and the dynamics between researchers and research subjects. In Medellín I saw a lot of very moving conversations, and also what is sometimes called the “therapeutic misconception,” in which a person who is being studied believes, or is led to believe, that they are being cared for, which is not the same thing. It happens all over the world in rare disease research, especially when there are no therapies to offer and research provides a very needed form of human attention.

I also came to conclude that some of the conventional wisdom around clinical trials should be revisited. Namely, the idea that offering material help to people, especially poor people, who take part in studies constitutes “enticing” them. That is how the drug companies and a lot of the people running clinical trials think. The clinical drug trial I followed in Colombia had a budget of $150 million, yet only about $150,000 was earmarked every year for helping the families, and a lot of that went to staff salaries. Even then there was still a lot of debate about whether or not this modest little program could be deemed an “enticement.”

There are many ways to help this community that would not mean cash rewards to individuals. Scholarships for young people who have had to stop studying while nursing a sick parent, dedicated nursing homes, a 24-hour call center for families in crisis – all these and much more are well within the means of multinational pharmaceutical firms.

While this book is centered around a very specific community, Alzheimer’s affects almost 7 million people in the United States. How has the work being done there affected Alzheimer’s research?

The Colombian families have contributed an enormous amount to global Alzheimer’s research since the 1980s. Studies on them in the 1990s confirmed that the mutations on the presenilin-1 gene caused most cases of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease worldwide. Work with their brains and tissues helped develop the dominant, if flawed, hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease, which says that a protein called amyloid-beta sparks the disease cascade. More recently they’re contributing a ton of information on the genetics of Alzheimer’s. Because some of the people with the mutation get sick much later than they’re supposed to, they’re offering new evidence for genes that actually confer resistance to Alzheimer’s. Those findings will be used to create better drugs. Meanwhile, a variety of Alzheimer’s drugs will be tested in them in the coming years, because even though Dr. Lopera sadly passed away in September 2024, his colleagues are carrying his work forward.

If anything, the work on the Colombian families may be overly focused on mining them for insights that can be applied to late-onset Alzheimer’s disease, which is much, much more common. Right now, the Colombian families are a laboratory—for other people. But the genetic form of Alzheimer’s they have, I would argue, is even more catastrophic than the norm. It cuts down people in the prime of their lives. It pulls families apart, causes terrible psychological and financial strain, and robs young people of their parents and their confidence for the future. I’d like to see these families become a laboratory for themselves.

What did you find most surprising as you researched this book?

When I started working on this book I had just turned 44—the same age most affected people in the Colombian families begin to develop the first symptoms of the disease. I thought that being around people my own age, who were suffering a disease normally associated with old age, would be very moving to me and that I would have a lot in common with them. But as it happened, I tended to relate better to their kids—the young adults in their twenties and early thirties, who had grown up in the city and had more options and education their parents did. They spoke and thought differently. I found them really struggling with how to think about this disease, what the researchers really wanted from them, and whether they should find out whether they carried this horrible mutation, all the while harboring important personal and professional ambitions. And so, to a great degree, this came to be their story.

Jennie Erin Smith is the author of Valley of Forgetting. Her previous book, Stolen World, was named as a notable book of the year by The New Yorker and The Washington Post. She is a regular contributor to The New York Times and has written extensively on nature, medicine and Latin America for The Wall Street Journal, The Times Literary Supplement, The New Yorker and others.

Jennie lives in Florida and Colombia. In 2018 she moved to Medellín, where she spent six years researching Valley of Forgetting. Her work took her into the homes of patients; the clinics where doctors studied them; the brain autopsies of those who had died; and into the countryside, with rural families that have lived with this disease since at least the 18th century.

She is a recipient of the Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award, the Waldo Proffitt Award for Excellence in Environmental Journalism in Florida, and two first-place awards from the Society for Features Journalism.

Learn more about her writing on Alzheimer's disease below.

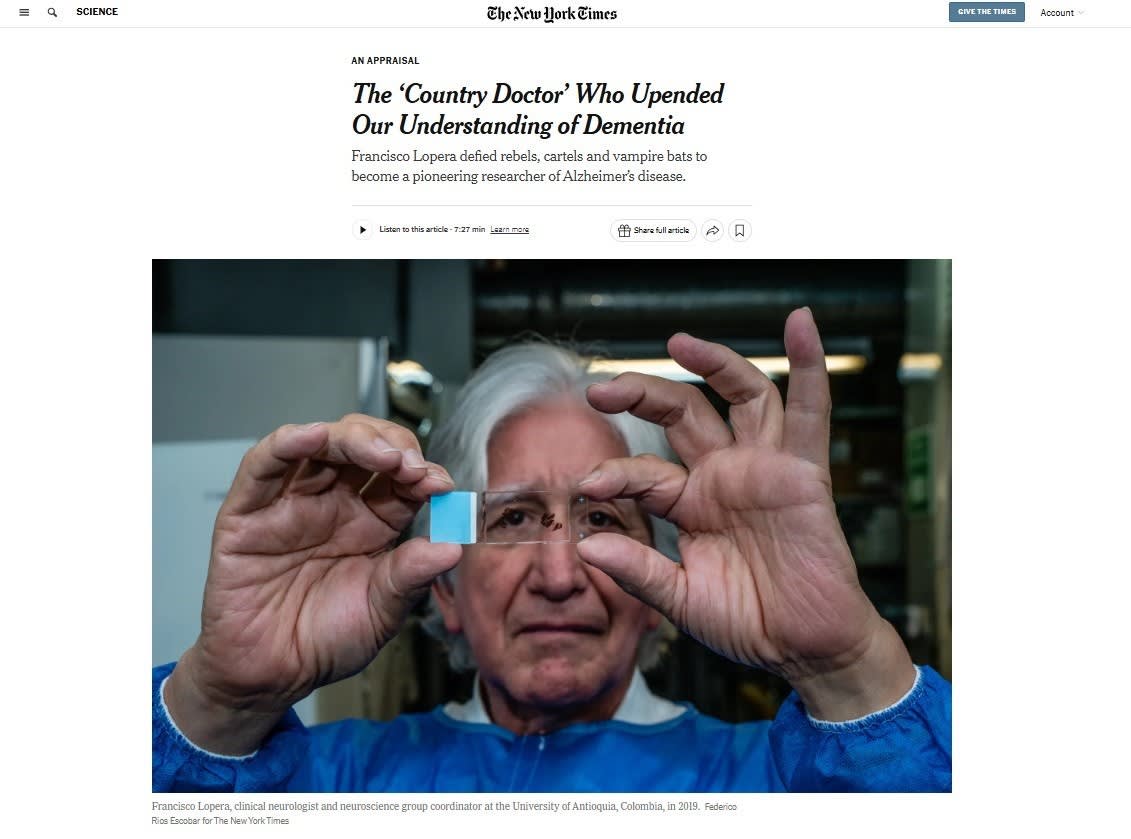

After neurologist Francisco Lopera passed away in September 2024, Smith wrote for the New York Times about his decades of research into the secrets of Alzheimer's disease. The stories of Lopera and the families he treated form the heart of Valley of Forgetting.

Like many people in the remote mountains of Colombia near Medellín, Aliria Rosa Piedrahita de Villegas carried a rare genetic mutation that causes early-onset Alzheimer's. In a 2020 article for the New York Times, Smith wrote about her unique case and its impact on Lopera's research.

For publicity inquiries, contact:

Shailyn Tavella | stavella@penguinrandomhouse.com

Riverhead Books