Reader's Guide to The Empathy Diaries by Sherry Turkle

Dear Readers,

Welcome to The Empathy Diaries. I am excited to share my book with you because writing it was such a journey for me and I imagined my readers coming to new ways of thinking about their lives as they read it. About love and work. About personal and professional choices.

I had a set of questions as I wrote the book that helped me to give it shape. And they helped me to think about my life more deeply. I hoped that readers might find them useful as well.

● I had special objects that brought me back to places and memories of my childhood and growing up. Readers: Do you have such objects?

● My family had secrets that were part of who we “were” as a family? They came to seem so natural that my family never considered what keeping them was doing to me. Readers: Do you have family secrets that have held you back? Did you have secrets you moved beyond?

● I had important mentors. I didn’t always realize their impact at the time. One of my great regrets is that in some cases, I never said a proper thank you. Readers: Do you have people who are helping you? Are you acknowledging them?

● In my case, setbacks propelled me forward and taught me that I was more resilient than I thought. Readers: Could this be true of you?

● I tell the story of how my personal and intellectual life became enmeshed. I fell in love with ideas that in some ways enabled me to “think through” issues raised by my personal story. Readers: Do the pieces of your life fit together in ways that you might not have considered before?

● There are key moments in The Empathy Diaries where I admit that I consciously did not “know” the truth, but when I learned it, I had the distinct feeling that I had known it all along. Readers: Are there things you know but cannot say?

I hope you enjoy my story and learning about some of the extraordinary people and ideas I met along the way. Enjoy! And for more writing of mine provoked by The Empathy Diaries, you can visit my author’s page, sherryturkle.com.

Warmly,

Sherry Turkle

Q&A with Sherry Turkle

Your book is titled The Empathy Diaries, what is so crucial and enduring about empathy to you?

This book is about how I learned to be a friend, a better listener, how I learned how empathy requires the capacity for solitude. As technology progressed to undermine the private spaces of our lives, I determined that when you undermine privacy, you undermine empathy, democracy, and intimacy. My personal and political passions became one.

As my career developed, I came to see empathy under attack by the imperialism of artificial intelligence. AI researchers put forth the idea that machines, like people, could have it. I see empathy as something only people have, the outcome of having a life, a body, having grown up from being little to becoming older, of knowing pain, of fearing death. If you want to solve an equation, you might turn to an artificial mind. If you want to discuss love and loss, turn to a person.

You’ve written the story of finding your way in your professional world. What is your advice to others trying to do the same?

Successful careers have origin stories. My book is about how my work became “lit from within” because of its connection to my personal journey. Work becomes tied up in attachments losses, in sum, the people we connect to and the people we lose. My story is particular and has its own dramatic arc—a rogue scientist father who used me for psychological experiments and then disappeared from my life, a mother who was ashamed of this story and made me promise never to speak about it. She took things to an extreme: We really never spoke of this father and I had to lie about his name, my name. I learned empathy because I knew that my mother loved me. I needed to figure out why she would do this to me, even as she loved me so. So the story that ties together my career and my personal life is dramatic. But my message is that every career has a story, even if less dramatic. At one point in the book I say: “We love the obects we think with; we think with the objects we love.” We are attached to people and ideas and objects. We make careers that try to stay close to them in one way or another.

We are often motivated because we are working out the stories of our life. I had talents, but I also had insecurities. If I were giving advice I would say: Don’t be afraid to learn about your insecurities as well a strengths. They’ll both help you forge a career that is uniquely yours. Develop confidence in your own style of creativity. And perhaps most of all, develop the capacity for creative solitude.

The book vividly takes the reader back in time—how did you achieve that?

I reached out to people from every phase of my life. From fifth grade classmates to my colleagues from my early days at MIT. I wanted to check my recollections against their impressions of me at the time. I went back to Wolozin, Belaurus, where the Bunowitz (turned into Bonowitz) family was from—at the Wolozin yeshiva, I found the names of my ancestors engraved on its walls from when they were students. Seeing these names made that connection to Wolozin all the more real to me. Of course, I also went to Hoboken in New Jersey and Dekalb Avenue in Brooklyn, where my grandparents’ families settled in America. Thanks to Google, I could step out of my grandmother’s home in Hoboken and see the streetscape as she had seen it.

I had reunions of my fifth grade, junior high school, high school, and college classmates. I went to the 100th birthday party of my Aunt Mildred’s best friend, one she travelled with and who was a frequent companion at the theater. I talked to my mother’s doctor during her final illness. I was racing against time. Many of the people I spoke with, died shortly after I reached them. I can only say that I immersed myself best I could in the story of my life and tried to honestly re-experience it.

“Evocative objects” anchor many of the chapters. Can you say more about their importance to both your life and your work?

I do a lot of writing in the book about the power of objects. How they carry memories and ideas. How we use them to think through things. My grandmother considered her set of dishes her treasure, a link to her mother, to her children, to her grandchildren, and to her great grandchildren, whether or not she met them. She thought her dishes were so beautiful that these great grandchildren would be eating on her dishes on Jewish holidays. When she saw the dishes, she saw her future. She is right. I use those dishes. I am starting to share them with my daughter who also uses them on special occasions. Now, my daughter is pregnant with a girl. It gives me goose bumps to think that she will use the dishes too.

I love to talk about what objects mean in the lives of individuals and families. I hope my reader also learns how to use objects “to think with” as I narrate how I put that story together for myself.

Discussion Questions

My mother kept me from my father because she feared him. She had caught him performing psychological experiments on me. How does this early revelation color your reading The Empathy Diaries? It begins, after all, with a man who is the opposite of empathic.

I searched for my identity in a “memory closet,” where I found a photograph of my never-spoken-of-father with his face blacked out. It gave me a lifelong interest in searching for meaning in concrete objects. Do you have objects of childhood that were precious to you the way the objects of the memory closet were to me?

Living as a Bonowitz, I was secretive. Living as a Turkle, I was anxious. I fantasized (wished for?) invisibility as I longed for empathy. How do I handle these feelings and frustrations to find greater satisfactions?

Why does studying from “review books” make me feel fraudulent in school despite my hard work? What does this suggest about what kind of teacher I’m going to be, what kind of educational philosophy I will be drawn to?

Why is the notion of “decountrifying” so useful to me?

I describe several college courses that I still believe taught me how to think. What were the merits of these courses? I seem less interested in content than thinking about thinking.

When I learn my mother is dying, I face that on some level, I am not surprised. How do I try to think about the things we know but cannot say?

I was drawn to studying people on the margins of things. Do you think, in doing so, I was trying to think more deeply about myself?

I describe the contribution of mentors. What did they each provide? What does my experience suggest about the importance of face-to-face conversation in education?

Jacques Lacan wants to destroy the notion of a privileged “discourse of the master,” yet at his school, he is very much in the position of “thought master.” Many large organizations seem to this conflict. Do you come to this book with your own examples in mind?

The scene when my grandfather insists that my grandmother will not have home nurses cuts through my idealizations of him. Reading back, does this scene illuminate earlier episodes of Bonowitz life, including perhaps, my mother’s haste to marry Milton?

I try to capture the moment of infatuation even if one suspects one’s choice may not be wise. I tried many strategies before settling on my final choice of replicating the conversation, topic by topic. Discuss my choice. Compare it to other possible strategies.

When I take Seymour home to meet my grandfather, their encounter illustrates Seymour’s gifts as a teacher. He charms my grandfather with a juggling lesson. What elements of pedagogical strategy does Seymour bring together in that lesson?

I describe my early days of teaching and asking my students to write “object papers,” papers that describe a fist object that was important in their lives: a spalding ball, a baseball mitt, a set of jacks, a deck of cards. Readers: Do you have an early object that influenced your later thinking and feeling?

I finally visit Charlie. I think it’s important that in the end, I ask Seymour to join me. Yet I am also shocked by a certain “similarity” between the two men. The comparison is unfair. Seymour is a world class scientist. Charlie, a crank. But my mind plays tricks with me and sees odd similarities. As a reader, could you empathize with my feelings?

I have a showdown with Charlie when he tries to interfere with my MIT life. It ends our connection, after all the effort I put in to find him. Could I have handled things better?

I have a showdown with MIT, which ends up firing me before I get them to rehire me. I draw some practical lessons from my struggle. Would you choose others?

I worry about a flight from conversation as people would rather text than talk and a new kind of isolation as we turn to screens instead of each other… or turn to each other via screens. I write of “the illusion of companionship without the demands of friendship.” On social media we can feel close but not vulnerable. Does this correspond to your experience of new media?

What are the benefits of seeking out experiences where you are a “stranger to your own voice?”

Kugel Recipe

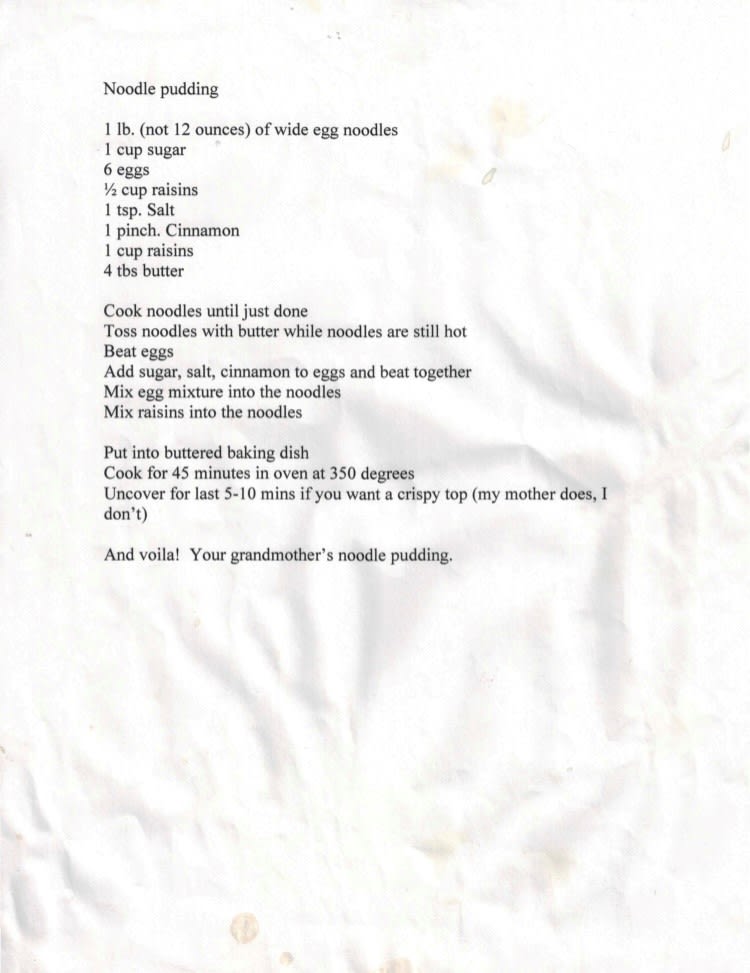

Readers of The Empathy Diaries may want to make my grandmother’s delicious noodle kugel and drink it with wine or coffee. It is delicious hot or cold. I thought this recipe was lost, until a close friend retrieved it for me— on the back of a box of egg noodles. It made sense that my grandmother’s recipe was not passed down from her mother (who had a cook!) but from a carton of noodles. It is my friend who writes: “And le voilà. Your grandmother’s kugel pudding.” This is a photograph of the recipe in my kitchen, so you see the stains from much cooking! I make it on all Jewish holidays, but on Thanksgiving too and whenever I want to perk up a chicken dinner with a little Bonowitz feeling.